CLIMATE ACTION IN AFRICA

By Alex Makotose

African countries have fewer resources and the capacity to mitigate and manage the effects of climate change compared to other regions. So what does Climate Action look like in Africa is today; its effects, context specific solutions and sustainable practices to survive this rising crisis.

A “code red for humanity” has been issued and Africa will be the most hit. African countries contribute less than 4% of global carbon emissions responsible for climate change yet they are currently and will be the most affected region. Rising temperatures and sea levels, changing rainfall patterns and more extreme weather will impact livelihoods and communities, infrastructure, national budgets and socio-economic development. Recent headlines have called the world's first climate change-induced famine in Madagascar, where back-to-back droughts have pushed communities to the very edge of starvation. Elsewhere in southern Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe were the two countries most affected by extreme weather events in 2019 according to The Global Climate Risk Index 2020. The latest report from The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts these events to worsen if we do not act.

Compared to other regions, African countries have fewer resources and the capacity to mitigate and manage the effects of climate change. This, however, has not stopped countries from contributing to climate change efforts through pledges to reduce carbon emissions, and communities coming together to adapt safe and sustainable agricultural and environmental practices.

Can Africa develop without fossil fuels?

The main cause of climate change is the burning of fossil fuels, mainly petroleum, coal and natural gas which produces carbon dioxide (CO2). Fossil fuels are responsible for humanity’s rapid industrialisation going back to the use of coal in the Industrial Revolution which started in Europe . Our energy consumption, in Africa and globally, is dependent on fossil fuels. The proposed solution to this very real threat is strong and sustained reductions in emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. In other words, we must stop burning fossil fuels and turn to renewable and clean energy sources (solar, hydropower, geothermal, wind and biomass). This is a big ask, not just for the developed but also for developing countries that must drastically increase their energy production to meet growing demand.

Many African countries have demonstrated political will to join climate action efforts by signing and ratifying the Paris Agreement, the first-ever legally binding global climate change agreement, adopted at the Paris climate conference (COP21) in December 2015. The main goal of the Agreement is to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2 degrees Celsius, preferably to 1.5 degrees. As part of this, countries are required to prepare, communicate and maintain nationally determined contributions to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. Ultimately, African countries have signed up to reduce fossil emissions, perhaps to their detriment. The question is can this be done, and is this fair?

Today some 600 million people do not have access to electricity and African countries are grappling to provide cheap accessible energy to their growing population. Many African countries have natural reserves of oil and natural gas which are key to economic development, not just for domestic energy production but also for global consumption and foreign investment. The call to reach net-zero by 2050 asks for transition in the energy sector which requires economic and social system changes. African countries must do what no other countries have done before; develop without the use of fossil fuels.

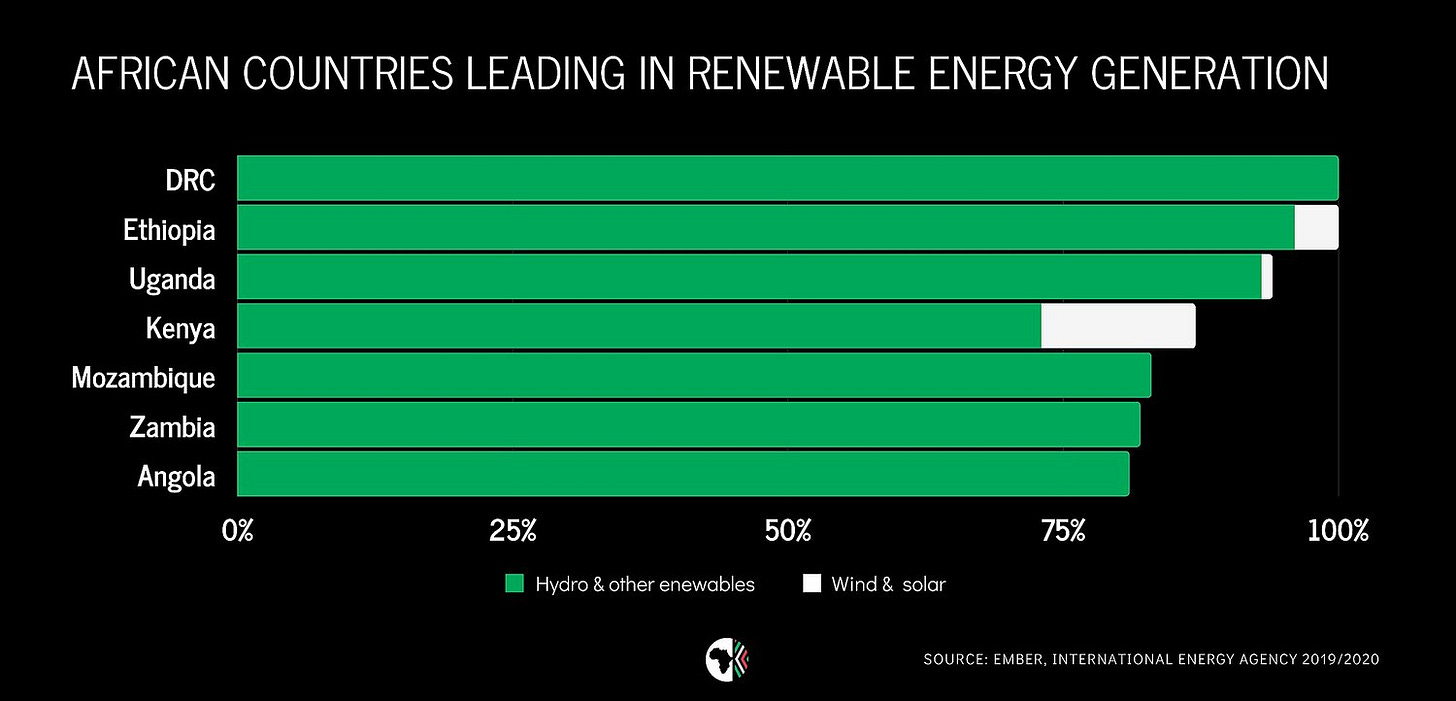

A look at Kenya’s ambitious plans to achieve 100% green energy suggests this is possible. In 2018, Kenya’s president announced plans to move the country to 100% green energy by 2020. Although this goal was missed, over 73% of Kenya’s energy is from renewable sources. Kenya boasts of being the largest geothermal power producer in Africa as well as having the largest wind power plant in Africa. Other countries leading in clean energy are DRC, Ethiopia, Uganda, Mozambique, Zambia and Angola which generate over 80% of their electricity from clean and renewable sources. Perhaps, following in their footsteps, others can leapfrog from using fossil fuels to renewable energy in a similar manner to how Nigeria and other countries went straight to mobile telephony without going through the fixed-line stage.

Ultimately, individual countries must consider their unique technological, geographic and social circumstances in their strategies to reduce carbon emissions. Such strategies must include policies that incentivise renewable energy use, enabling legal frameworks, financing mechanisms; and electricity supply strategies that prioritise renewable energy sources.

Community driven climate action

The climate change conversation is guilty of not only focusing on developed countries but also of silencing the voices and perspectives of those most affected. The public and grassroots movements have an important role to play in the development of energy policy and operation of the energy market. Public reception to climate change action is important because of its relationship to policy making, especially in democratic societies.

Across Africa, communities have long identified the impact of climate change and have been adapting and building resilience. Deforestation, the loss of forest areas around the world, is the second cause of climate change which both government and civil society are rallying to tackle. Trees filter CO2 from the atmosphere which is released back into the atmosphere when trees are cut and burned. Reforestation, the process of replanting trees, is the solution to this which is much less problematic than the reduction of fossil fuels albeit not without its complexities.

Qaamqaam, a village in Somalia, is known for its thick, drought-resistant acacia trees, the backbone of Somalia’s multimillion-dollar illicit charcoal trade. To fight deforestation, the village has employed a unique approach blending customary law, Islamic law and environmental protection law to create a strict hybrid legal system that criminalises the cutting and burning of trees.

In other areas, donor-funded projects perpetuate a top-down approach to the climate change conversation. However, there are some success stories anchored on community buy-in. For example in Sierra Leone where the coastline is sinking further each year, following initial apprehension, over 55% of rice farmers have pledged to integrate mangroves into their fields instead of cutting down trees to build fences.

Context specific solutions

Alongside government actions and donor funded projects, there is a growing number of young African activists challenging governments and businesses to take stronger measures for adapting and mitigating the impact of climate change. Social entrepreneurs are also championing environmentally friendly practices and developing environment-conscious innovations and business models. It is in this spirit that this issue, “Climate Change and the African Solution,” will engage with the questions raised above, specifically how governments and businesses are responding to the global call to take action now. It will also explore key issues related to climate change justice and the reality of climate change across the continent.

Alex Makotose is a law graduate who has provided intellectual property management and strategy design support to research and commercial projects within life sciences and agricultural sectors across Africa.